FRED PHILLIPS

Fred Phillips is the founder and Principal of Fred Phillips Consulting. He has won numerous awards for his large scale restoration projects and his work has been featured in a variety publications, including The New Yorker, Landscape Architecture Magazine, Restoration Ecology, Outside Magazine, and Arizona Highways.

Within the realms of Landscape Architecture and Ecological Restoration, Fred Phillips is a bit of a legend for his on-the-ground approach to design. For over two decades now, Fred has carved his own path - interweaving design, community growth and restoration together across large-scale projects throughout the West and abroad. Fred began his career working with the Colorado River Indian Tribes, leading the design for the 1,042-acre Ahakhav Tribal Preserve on the Colorado River Indian Reservation. Since then, he has largely overseen the planning, design, and implementation of more than 12,000 acres of wetland and riparian habitat and stream restoration projects. He has also directed millions of acres of restoration and conservation master plans. With each project, Fred embeds himself in the landscape and community he is working with, and it is not uncommon for Fred to set up camp on the site for a number of years.

It was a delight speaking with Fred about how he started his practice, his advice for students and young practitioners, and his visions for healing the land. Our conversation stretched from getting kicked out of a landscape architecture program to restoring 8,000 of Navajo canyonland, with lots in between.

Fred Phillips, Founder and Principal, Fred Phillips Consulting

You have spent nearly 30 years working on large-scale ecological restoration projects throughout the country, and internationally. Can you talk about how you got into this work? What have been your most pivotal projects thus far?

I've definitely taken a more nontraditional route in landscape architecture and life. When I was at Purdue, I struggled my first couple of years in school just with getting my bearings on what I really wanted to do. However, while I was doing public service volunteer hours (planting trees on the side of a highway because I had made some bad decisions), I met one of my professors, Bernie Dahl. Bernie was the chair of the landscape architecture program, and he was nontraditional as well. He was the guy that would come in wearing one of those Russian winter hats, all bundled up, and he would always talk about tribes and restoration.

After I got kicked out of the Purdue landscape architecture program because of my grades and once again, some bad decisions, I redid my sophomore year. I really gravitated to Bernie during this time because he was about working with communities and looking at regions and watersheds - not just backyards. When I was a junior, I met another interesting individual named Benjamin Frederick Samuel. He was one of those guys that had gotten many PhD’s from all around the world. He was just fascinated with everything. I got to talking to him about how I was into rivers and how Native American wisdom and culture really always interested me. And he was like, “I know this tribe out in Arizona that needs to restore this stretch of river, and they could really use someone like you.”

He gave me the number of the Chairman of the tribe, and I gave him a call. At this time, I was 23, at Purdue, and I had a pretty strong feeling that that call was going to change my life. And it really did. The Chairman of the tribe said, “we do want to build a park and do something with the river, we just don't know what. If you want to come out here for the summer, we can give you a space to work and you can do what you do.” He didn't really have high expectations. I drove out to Arizona, to the Colorado River Indian Tribes, and we cleaned out this old kindergarten room for me to work in. I had these really short desks and really small chairs and just started drawing and talking to him, the tribal elders and the tribal community.

I started to add another layer by talking to the Bureau of Reclamation, Fish and Wildlife, and the land agencies around there. I came up with this vision for 1,000 acres to re-meander the Colorado and do some old oxbows that have been levied off. I dreamed big with it: let's build a native plant nursery, let's build 4 miles of trails, let's have an environmental ed program, let's do all of that. I showed the tribal council the design of the Ahakhav Tribal Preserve, and they're like, “Cool drawing, kid. Good luck back at school, thank you for your time.” I went back to Purdue and was finishing my senior year, when Chairman Dennis Patch called me to say they wanted me to come out and get the project going. I flew back out on my spring break, wrote a $50,000 grant (Bernie had taught me how to write grants during lunchtimes at school), flew back to Purdue, and we got the $50,000 grant. A young landscape architect, Adam Perillo and his now-wife, Sonia Perillo, a wildlife biologist wanted to come help me. So Adam packed up his computer, Sonia got her books, and we all drove out to Arizona. We took the concept vision, and we turned it into a refined document with existing conditions, history, geology, water quality, all that. While we were doing that, we started writing grants.

In the 1960s, there was a thing called the Colorado River Front Work and Levee Act, where they basically channelized and levied the whole river. When they did that, the Bureau of Reclamation claimed it would restore four backwaters to mitigate the impacts from that project. It turns out that they only restored one or two backwaters. So I went with Chairman Patch to the Bureau of Reclamation and we told BOR, “ hey, we have this plan to restore this backwater. You guys had stated in this document you would do this 40 years ago.” He kind of scratched his head and then said, ”well, if you guys can come up with half the money, we'll pay for the other half, and we'll get it done.” That's how we excavated 300,000 yards and reconnected these historic channels and protected it from water skiers and motorboaters. Meanwhile, we had also built this little park with $50,000. The tribe now had a place on the river to do ceremonies and hold events. We started the Youth Cultural Fest and had students from twelve different countries and four Indian tribes. Fast forward five years and we had raised about $5 million, restored and protected 1000 acres of land, built a four mile trail system, established a native plant nursery that was selling 50,000 trees a year, and started an environmental education program.

I learned a lot about grants. I learned about working with communities. I learned how awesome and inspiring it was to get to work with the tribe and get to know some of their wisdom and challenges and elders. The other really important part that really guided me after those five years was having to essentially build my own department within the Tribe , dealing with contracts, insurance, employees, equipment, what you would need to run a private firm. It was just like the best place in the world to cut my teeth, to do ecological restoration, and learn how to build a small practice.

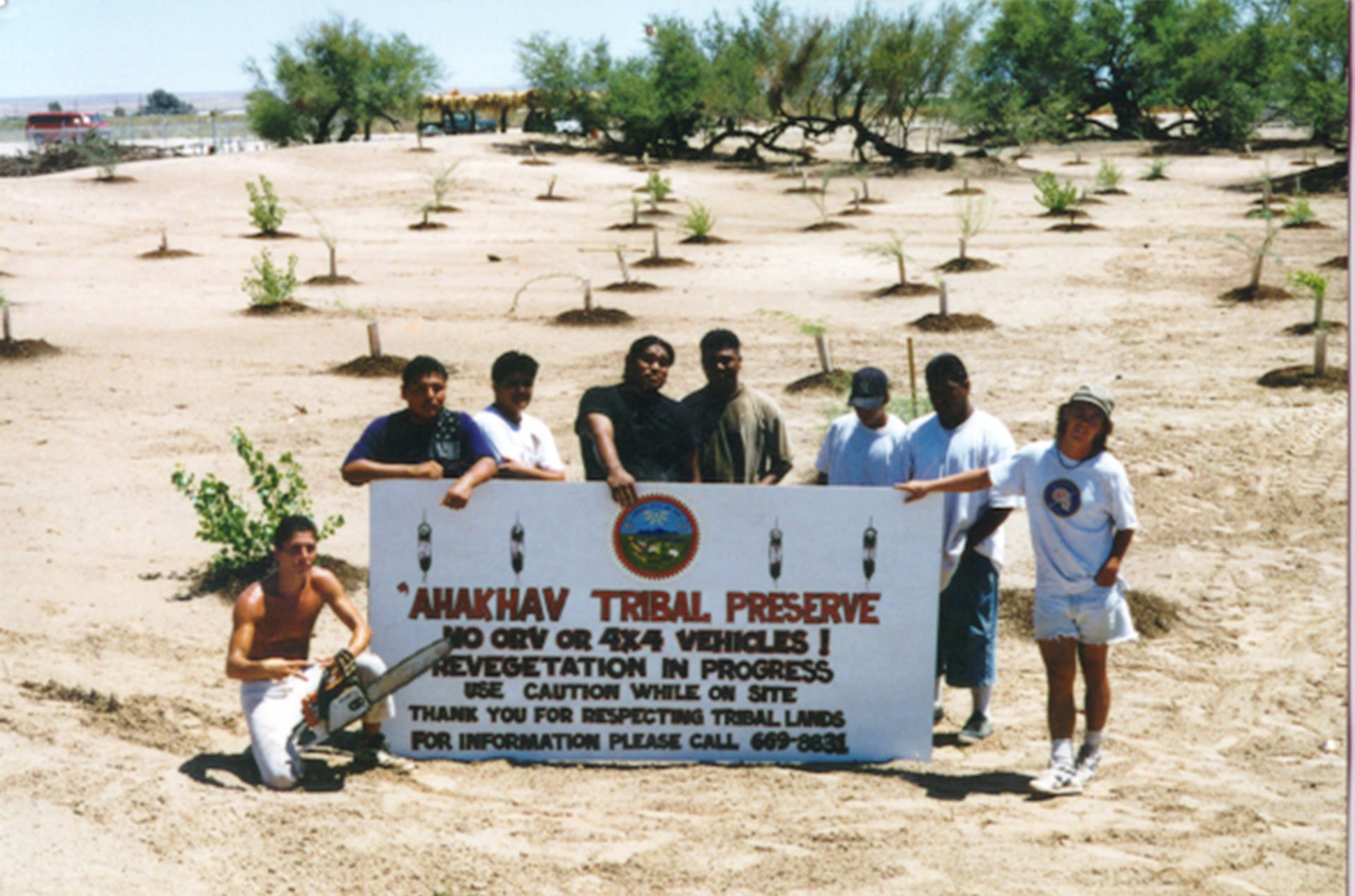

`Ahakhav Tribal Preserve | Fred and staff prepared the `Ahakhav Tribal Preserve Restoration Plan in 1995. Throughout the five years of the porject, the team secured more than $5.7 million in grants. The ‘Ahakhav Tribal Preserve now hosts over 1,000 acres of restored cottonwood/willow and wetland habitat, miles of protected and restored backwaters, miles of nature trails, a native plant nursery, and a 4-acre nature park used by the tribes for various community and social events.

What is your process for beginning a project in a rural community? How do you gain the proper knowledge and trust of a community when you're often coming from the outside?

When you go to work in a community where you're the minority, it's a very educating, enlightening experience. Right now we’re working with the First Mesa Consolidated Villages of the Hopi Tribe. It took a couple of years of just meeting and talking with them to gain the trust of that community. As an outsider, I work with a foundation. It started with just going and meeting them and breaking bread and asking them how they would like to proceed. And beautifully, the late John Scott Sr., a Hopi Navajo elder from First Mesa whom I'd gotten to know when I lived in Parker, had connected me with some of his relatives when he was alive, the Collateta family. I offered the clan chiefs tobacco offerings (because that is a traditional offering within the Hopi culture), and just from these initial historic connections and building of trust, they asked me about writing a grant and restoring the Pongsikya Canyon (colonially named “Keams Canyon).

The project is guided by the clan Chiefs. We sit with them and ask them what they see happening there and what they would like to see happen. Pongsikva has many springs and sacred sites. This cultural resource - with its spiritual medicine, birds, butterflies, springs and plants - is a very important area to the First Mesa Consolidated Villages of the Hopi Tribe. The Canyon also has an old boarding school, with some historic karma that needs to be healed. There’s a lot of healing that needs to happen. The tribe wants to protect the springs and the vegetation in a more sustainable way, create a place to walk and recreate, and begin to heal what went on with the boarding schools. We’ve spent days walking the site and looking at the springs, the vegetation, and the geomorphology of the historic dam and beaver ponds. And we’ve looked at the standard landscape architecture data - topography, water quality, the dam report, etc.

Now we'll start putting all those pieces together: “How can we create a place where we can create a deeper water habitat, not just have it fill in every year? These areas are off limits because they're important cultural areas. This is where we think we could have a community gathering area. Let's close the highway next to it and just get rid of the road altogether because the whole area is really important spiritually for the tribes.”

I always try not to get too far on designs with anybody, whether it's my neighbor or a tribe, before we sit down and get their reaction to what we've put together. That's when you get into where the heavy lifting is going to occur.

Where can we do light touches on the land? Where do we want to put a place for the people to gather? Where do we want trails? How can we harvest sustainably from these other areas as opposed to buying it from a nursery in Phoenix or a big city? Where are the stands of healthy plants and seeds that we can harvest from this site and use there without having to go outside? On the other end, the tribe really wants this plant and it's not here. Where's the closest area from here that we can get that plant? If we can't find a place to get it, then where can we find the nearest genetic source to that? Well, let's build a nursery. Let's just do it right here. Does the tribe have a conservation corps? Are there other tribal contractors that are doing this work, doing the water, harvesting erosion? Where are the gaps on how we're going to get this built?

If there are nesting sites, or there are certain things like, just hands off. Where do we not touch this? I think our job is to help Mother earth heal and do her processes and not come in and just try to change everything. Where can you do this by hand? Where can you do it by just simply resting it, by getting livestock off it or not harvesting it? Where are the big treatments needed? In concert with that, we're looking for funding and we’re getting permits.

Most importantly, I follow the lead of the traditional leaders and the tribe.

I think it goes across the board, whether it's grandma's backyard or a tribe or federal agency or some big fancy mitigation project. How can you start doing things now to get people excited about it? Because plenty of people have seen a big fancy plan get thrown on their table and not get done. Can we get the elders to come out and cook some fry bread in one of the spots they really like and have them talk to us about the plants? Can we just go cut some willows and plant them in one spot? Can we get funding to build a half acre park so there's some grass and some shade and some place where people can start reconnecting with this place?

I found that if you take the time and have a little patience, building local capacity will lead to a stronger, more resilient future, not only for the landscape, but for the people. They say, heal the land, heal the people. I've seen it happen many times and with myself as well.

Colorado River Indian Tribes (CRIT) Western Boundary Conservation Plan |Fred Phillips Consulting and CRIT collaborated to develop a comprehensive plan that protects and restores the regions wetlands, mesquite bosques, and cottonwood forests while also accommodating over 3,000 acres of hemp, potato, nuts, and specialty crop farming using no-till conservation agricultural principles. Native pollinator habitat gardens will inhabit the spaces between crops, simultaneously boosting ecosystem diversity and crop yield. To bolster CRIT’s economic sustainability, the master plan establishes a quarter-mile commercial easement and a 40+ mile riverfront greenway trail along the Colorado River.

In many ways, you’ve taken the road less traveled with your career. How has that benefited your work and the people and communities you work with? What does it take to walk an alternative path outside the typical landscape architecture trajectory?

I think madness helps. And I think any path you take is going to be challenging. As I mentioned before, for me, making that one call to the tribe in Arizona changed my life. Just that one question and getting that one phone number and making that call is what started it all off. So I'd say number one is seeing an open door, and kicking the door down.

I’m moved to do this. I want to do it. Not all of the paths are going to be fruitful, but there will be some that are. I think if you really follow what you want to do in your heart, that's going to be your career and you stick with it. With that first job in Arizona, I wasn't making much money and it was difficult at times, culturally, physically, emotionally. But I got to build this amazing project and got to know so many amazing people. That was the worth to me, that was the wealth in all of it. I think a lot of young practitioners bounce from place to place. If you're in a place that you don't like and it's not inspiring you and it's not what you want to be doing, don't do it. If you're in a spot where you're doing something good and you're digging it, it's not going to be easy, but stick with it for a while.

I've always really liked that part of my path. If I was young again, I wouldn't do it any differently. Long ago, I worked in a firm in London, and they just did EIS’s on big road projects, and although I liked the people I worked with, I was totally uninspired by the work. Be picky about where you start. Take your time with it. We all have student loans and we all have bills to pay, but don't just go jumping into the first thing just because you think you have to. Get that practical experience. I've definitely dove into plenty of projects where I didn't know exactly how to do it. Like this range restoration at Navajo Nation. I don't like fences, and I don't like building fences. When I saw that we can get the wild horses and cows off of 8,000 acres and watch 8,000 acres come back to life in an incredible fashion by simply getting them out by building a range fence, I said lets do this! I found a bunch of great Navajo people and we figured out how to build a fence across the canyon. It was hard, but it was really cool. It's like,” oh, I can see how this is going to help everything. I'm going to figure out how to build a fence and I want to do that with local people so they can continue when we are finished.”

Yuma East Wetlands Restoration | This 1,400-acre wetlands along the lower Colorado River was one of the most ecologically altered wetland landscapes of the Southwest- damaged by channelization, flow regulation, non-native species invasion, deforestation, and wildfires. The Yuma East Wetlands Restoration Master Plan, designed and implemented by Fred Phillips Consulting, has resulted in many threatened and endangered species, including the Yuma clapper rail, yellow billed cuckoo, California leaf-nosed bat, and Yuma hispid cotton rat returning to the site. Just as importantly, the communities surrounding the river—Native American, Anglo, and Hispanic—have reconnected with this restored riverfront and now strongly cherish it.

You talked about the importance of relationship building and how developing a great team plays into your work. Can you elaborate?

From a business standpoint, as a firm, the more you have in house, the more autonomy you have in your practice or control- a biologist that can go out and do the endangered bird surveys, a landscape architect that can do the CAD and GIS analysis, a civil engineer that can do grading drawings and stamp work, the administrative staff working on getting proposals out the door. I really pushed hard on that my first fifteen years and I had a great internal team of folks. We weren't a one stop shop, but we did a lot of it inside and I’ve always looked for and hired the candidates that were hungry and excited about the work.

I've always liked having my office within walking distance from my house and not getting too big so I could keep my hands and heart in every project. I eventually ended up burning out, though. I didn't give up, but I definitely got worn out, started a family, and that became more important to me. Emerging from that, for the last three years, I've really started to team up a lot with people. Now, if I need endangered bird surveys, there's a whole army of one person shops that do owl surveys or tortoise surveys or endangered plant surveys. When it comes to writing, I always find a local editor. I've gone from doing it all in house to farming it out, which has been more fun because it's less responsibility on you. There's a lot of small businesses that are excited to work as teams.

I think it's also super important that you stay connected with your colleagues in your own shop. I'm glad our culture today is leaning more toward this, towards acceptance. I think healthy relationships within your firm, with healthy boundaries are vital. I've always said to my employees, “we're going to work together and we're going to be friends, but neither of us can ever take advantage of this friendship. If we do, it's going to erode.” Part of that is knowing someone’s strengths and weaknesses. Many of my interview questions come from this place- what do you hate doing? What are you really not good at? What are you really good at? What do you love doing? There are certain things I'm really not that good at, and I try not to do them, but sometimes you have to. I think having those perspectives and keeping those people thriving, they make your life better, your practice better.

Fortunately, all the work I have coming in now, I love. There isn't a single project I'm working on that I wouldn’t put myself into and behind, it has meant I’ve had to be selective. When I was a small firm, and maybe not paying the bills, someone comes in and says, “hey, can you do a wetland delineation on this 2000 acre development?” Big fees, lots of money, all that. I've always turned those down. I've always kept my focus on land conservation, restoration, and recreation. Doing that has really privileged me with the client base I have. I'm friends with all my clients, family with a good chunk of them, and I like that. It can get tricky sometimes, but that's how we grow when we get into those complex situations. Sometimes they don't work out. I've had employees and clients that haven't worked out, and that's okay. That happens and I've grown a lot from those hard experiences. I feel like I have a bigger heart and I've grown as a person from those. I don't know if I call them failures, but it just doesn't work out with some people- fellow employees, colleagues, subcontractors, or whoever.

It takes a little faith and lots of work to do this work, but so far, 52 years in, it's happening. I'm a believer in it, and I think you just have to keep working hard at these things. Nothing's going to come to you just sitting back. I sponsored a gym banner for my daughter Fayes 4th grade basketball team and I was looking for great inspirational quotes. The one I landed on was from LeBron James, “nothing is given, everything is earned.” I wasn’t really born with any great talents, but I think if you choose something and do the work, it’s going to be fruitful eventually, but you have to earn it.

Bangka/Belitung, Indonesia Mineland Reclamation | An intensive tin mining legacy in the region has left over a half million acres of degraded, polluted lands. Extensive planning and research yielded detailed plans of best practices for tin mining land, providing alternative livelihood options for Bangka residents, improved ecological health, and profitable agricultural opportunities.

What does your ideal future for the rural countryside look like?

Some of the phrases that pop into my head immediately are resiliency, ecological uplift, and a shift in thinking, especially in the west. As cliche as it may sound, I would hope that there would be some harmony between all of the conflicting politics and people, because we’ve spent so much time fighting.

It is good to rest land and do rotational grazing. Beavers can be helpful, not in all situations. A lot of ranchers in the west are finding out that the people that have water during this mega drought when they're making water calls are the people that have beavers. They're embracing that because water is life, and without that, you can't really do anything. I think we need more of a balanced approach. I don't think it can be one or the other. Beef is here to stay and so is ranching and farming. On the lower Colorado River, farmers are growing massive amounts of alfalfa that get shipped over to Japan and Saudi Arabia and use four times the water of other crops. How do we shift the thinking from doing ten cuts of alfalfa a year to growing potatoes or other more water efficient crops with more water efficient methods? In the Southwest, agriculture is 80% of the water use. How do we help farmers and ranchers figure out how to keep the ranch or farm? Just like restoration practitioners, they're working land. We know it means a lot to both of us, but how do you do it in a way that's realistic for the situation we're in?

I think this is what, the fifth or sixth mass extinction event going on now. We really need to protect public places. Of course there has to be a compromise in some areas, but we really need to protect more public ground. For example, the tram that they want to build into the bottom of the Grand Canyon and the three dams they want to put on the little Colorado River are just not the best solution. I'm pretty hard on some of that stuff. I'm working on a restoration plan with all of the landowners here on my stretch of the Uncompaghre River in Colorado. Some of them don't want to participate in the restoration. Okay, fair enough. There's many others that do. Figure out how we can accommodate for what people believe, because everybody is important.

A third of Arizona is tribal land and a lot of it is experiencing severe drought, desertification and overgrazing. We need to engage more with tribes. There were 1,200 acres that were just given back to a northwestern tribe from the Forest Service. It's their land now, so they can do what they want with it. They can start a mitigation bank. They can do restoration. They can burn and do agriculture like they did for centuries and make it healthy again. Tribal lands are a massive part of the West and we need to change many of the laws around them, one of them being the Real Estate Clause in the Clean Water Act. It's this perpetuity clause that prevents Native American tribes from participating in mitigation banking or conservation banking or carbon credits. They don't own the land, so they can't promise forever that they can do a permanent easement, or they can’t do a mitigation bank in perpetuity when some rancher that has 30,000 acres has really buggered up destroyed land. He can do a mitigation plan, he can get the credit, he can make $20,000 on the acre of the credit, and the tribes can't participate in that.

Tribes have a huge land mass. How do we engage with the Native American tribes on what they want to do and let them participate in the same things that private landowners get to do? I think that, to me, if there was one thing I could pick for the rural landscape of the West, that would be it. That and working with ranchers and protecting land. I have hope. I think we can do it. It's being done. It's just people got to eat. People got to have their vegetables and their steak and their Cheerios and all that. As a culture, if we want to have all these luxuries, these cars and everything else that I have and we have, how are we going to shift how we're doing things so that the land around us can support it?

I love this whole mantra of heal the land, heal the people. I love some wisdom that a Navajo woman named Renee Benally shared with us when we were doing the initial field work in Tegi canyon, “restoring this degraded, eroded, hammered canyon - bringing that back to life and lifting up the ecology, is bringing it back to beauty. It brings back the plant medicines, it brings back the food, it brings back the ability to graze it in the right way, and it brings back most of the ritual medicine that heals us as people.” It's beautiful wisdom. When the Navajos pray, they pray to beauty all around them, above and below them. And I would hope that we could bring ourselves and our land back to beauty. That would be my hope.

Text transcribed and edited from our conversation with Fred Phillips on January 26, 2023. Images provided by Fred Phillips.